This essay was written for the program book of the Opera Company of Brooklyn's concert performance of Mozart's The Abduction from the Seraglio (Die Entführung aus dem Serail)

|

| Wolfgang Mozart Posthumous portrait in oil Barbara Kraft, 1819 |

Wolfgang Mozart loved the human voice, and he loved to compose for it. Mozart’s special relationship with his singers, his unabashed love of the music of song, his intuitive understanding of vocal line and the interplay between different vocal ranges, his polyglot command of several languages and his brilliance as a musical dramatist, made him one of the greatest operatic composers in the Western canon. Yet, there is still a gnawing and unresolved issue in the meticulously examined life of this ineffable genius - Johannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart (1756-1791) - namely the waxing and waning of his popularity while he lived and after he died, tragically young and before his 36th birthday. This is nowhere more evident than in an examination of the history and public reception of one of his twenty-two fully produced operas, Die Entführung aus dem Serail - The Abduction from the Seraglio.

Today, an opera house can scarcely go through a season without mounting at least one Mozart work. Of the four most popular choices, Le Nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni, Cosi fan Tutte (the three iconic operas that Mozart composed with the marvelous Italian librettist Lorenzo da Ponte) and his penultimate opera, Die Zauberflote, one of these finely polished gems invariably shows up on the schedule each year of opera companies throughout the world, virtually assuring themselves of packed houses and highly favorable reviews. Even two of Mozart’s more impenetrable opera seria works, his first mature opera, Idomeneo, and his last opera, La Clemenza di Tito, are performed more frequently than ever before. And venues such as the Glyndebourne or Salzburg Festivals still find wonderful freshness in presenting rarer treasures like Mitridate, re di Ponte, Lucio Silla or Il Re Pastore from time to time.

We also happen to live in era of great Mozartean heroines – Diana Damrau, Miah Persson, Isabel Leonard, Elina Garanca, Cecilia Bartoli, Natalie Dessay, Renee Fleming, Joyce DiDonato, Barbara Frittoli – and heroes – Matthew Polenzani, Mariusz Kwiecien, Ian Bostridge, Peter Mattei, Ferrucio Furlanetto, Dwayne Croft, Kurt Rydl, Samuel Ramey and Ramon Vargas - to name but a few, allowing us unprecedented aural access to what Mozart was trying to achieve in the operatic genre; he certainly would have been delighted to work with these artists. In addition, the historically informed performance “HIP” movement has influenced how we take our Mozart. To be sure, HIP performances resonate most evidently in music of the Renaissance and Baroque (Monteverdi to Handel), but there are decidedly HIP-related influences in Mozartean orchestral and operatic performance, certainly in reduced orchestral size and a fastidious attention to tempi, if not the actual downward tuning of A from 440 Hz to 414 Hz .

This abundance of stellar vocal quality and Ürtext orchestral size and sound are part of the perennial popularity of many Mozart operas. Yet, there still remains an eight-hundred pound operatic gorilla in the room with tonight’s offering, Die Entführung aus dem Serail. How is it that during Mozart’s lifetime, Entfuhrung was his most financially successful opera, performed over one hundred times, and yet today, by a curious set of artistic and cultural circumstances, this delightful work, if not neglected, is certainly underperformed?

To answer this question, one must examine the historical and cultural context of Die Entführung, which actually began in 1778 with another Mozart opera remarkably like it. That Die Entführung clone, or better, Die Entführung prototype, was Zaide. And in examining Zaide, a torso really as Mozart never finished it, one can discern the catalysts that led to the creation of Die Entführung, namely the serendipitous confluence of Germanic national pride, the invention of German Singspiel, the popularity of “rescue” operas, and the rise of Orientalism that was all the rage in Europe in the late 18th and early 19th century.

From the beginning of the eighteenth century, most operas in Vienna as in much of central Europe were sung in Italian. These operas, whether they were comedies (opera buffa), serious morality plays (opera seria) or something in between (dramma giocoso), were largely written by Italian composers with Italian libretti. Even Handel, who was certainly not Italian (he was born in Halle, near Leipzig, indeed had some musical education in Italy, but lived most of his life in London) but who was most certainly a veritable rock star as an operatic composer, wrote his operas in Italian. Maybe that was why he was a rock star operatic composer.

Over time, this Italian hegemony over the cultural life of Vienna ate away at the pride of the Hapsburg rulers like a cancer. After all, before radio and television, what was there for the upper class to do at night but attend the opera? So it was that in 1778, Emperor Joseph II, in one of the many manifestations of his “enlightened absolutism”, hatched his plan. He ordered the creation of an artistic organization called the Nationalsingspiel , which was a company charged with the creation and performance of original musical works, all of which had to be comedies, written in German, and in a style called Singspiel. A Singspiel is literally a “song-play” and is similar to an operetta. The term “German Singspiel” is really a tautology as Singspiel existed only in the German language (Austria and Germany didn’t quite exist yet as actual countries, but rather were subsumed by the Hapsburg monarchy and their Holy Roman Empire), even if the Viennese chose to call some Italian operas, Italian Singspiele. Needless to say, Italians never did.

In a Singspiel, the story line is told by the “spiele” or words. The dialogue is spoken, not sung as it would be in the recitative of standard Italian opera. The arias and ensemble pieces do not advance the story; rather they just allow the singers to opine in song about the situation that the “spiel” put them in. Of course, Mozart being Mozart, the various arias and ensemble pieces in Entführung do advance the story a bit. Singspiel was a peculiarly Teutonic invention, and never quite resonated in those other operatic capitals, Italy and France. In fact, Die Entführung, the most enduring Singspiel ever written by anyone in history, was first premiered in Italy (as Il Seraglio) in 1935, fully 144 years after Mozart’s death !

With the creation of the Nationalsingspiel, its organizers went looking for composers and librettists to create original works in a new, indigenous “German Operatic Style.” Mozart, who was already trying to curry favor with the Viennese aristocracy even before he was unceremoniously booted from Salzburg in April 1781, tried his hand at the project, finding what he thought was a suitable libretto written by his father’s old friend, the trumpeter Andreas Schachtner, and began producing something quite remarkable. Schachtner’s libretto was originally entitled Das Serail, (The Harem), and in turn, this libretto stemmed from Voltaire’s 1732 tragedy Zaire (The Tragedy of Zara). Schachtner’s theme was also about a slave girl, in his case the slave Zaide, who was determined to rescue her lover, Gomatz, who had been imprisoned in the Sultan’s palace. Mozart wrote music for this libretto with a “rescue” opera theme, whereby the protagonist rescues their imprisoned lover. Mozart’s Singspiel was turning out to be a much more serious opera, and that was its fatal flaw, as the Emperor wanted comedies! Along the way, the production company got into financial difficulty and the whole project was scrapped. Mozart turned away from Zaide to pursue other compositions.

Mozart was angry about the whole matter, writing his father back in Salzburg that "The work (Zaide) was very good, but simply not right for Vienna, where they would rather watch comedies.” What has come down to us as Zaide is fifteen musical numbers, missing the overture, the end of the third act and final chorus. In the words of the eminent Mozart scholar Neal Zaslaw, "Zaide is a masterpiece-in-the-making truncated by circumstances." But all is not lost. Even though Zaide is rarely performed, the heroine Zaide’s sublime and poignant aria Ruhe Sanft, mein holdes leben (“Gently rest, my dearest love”) is still on many soprano recitals.

Yet, Mozart had been bitten by the Turkish bug. “Things Turkish” was a metaphor for the larger fascination for Middle Eastern culture that was invading Europe, even as the Ottoman Empire had been invading all of the Mideast! Various objets trouves such as Oriental fabrics, designs, foods and other “exotica” were very popular in Vienna and were making their way into central Europe, and those “rescue” operas became one extremely popular form of entertainment.

Fast forward to summer 1781: After leaving Salzburg and the domineering clutches of his father Leopold and his old boss, Archbishop Heironymus Colloredo (with a metaphorical and literal kick in the derriere by the Archbishop’s functionary, Count Arco), Mozart moved permanently to Vienna and very quickly befriended Gottfried Stephanie, the Inspector of the Nationalsingspiel, imploring him to find a suitable comic libretto. And Stephanie did just that. He borrowed from a story by Christoph Friderich Bretzner called Belmont und Konstanze. Stephanie doctored it a bit and refashioned it as Die Entführung aus dem Serail. Mozart liked the story very much (though he tweaked it continually as he was composing) working feverishly on it because he had a deadline. It appeared that Stephanie had wrangled a commission for Mozart from the Emperor, specifically for the arrival of the Russian ambassador, Grand Duke Paul, the son of Catherine the Great. The premiere was to have been in September. However, for some typically inexplicably Byzantine political reason, the ambassador did not show up as scheduled, and so the premiere was pushed back. Meanwhile, Mr. Bretzner complained loudly and in the newspapers of his original idea being stolen and plagiarized by Stephanie and Mozart !

Fast forward to summer 1781: After leaving Salzburg and the domineering clutches of his father Leopold and his old boss, Archbishop Heironymus Colloredo (with a metaphorical and literal kick in the derriere by the Archbishop’s functionary, Count Arco), Mozart moved permanently to Vienna and very quickly befriended Gottfried Stephanie, the Inspector of the Nationalsingspiel, imploring him to find a suitable comic libretto. And Stephanie did just that. He borrowed from a story by Christoph Friderich Bretzner called Belmont und Konstanze. Stephanie doctored it a bit and refashioned it as Die Entführung aus dem Serail. Mozart liked the story very much (though he tweaked it continually as he was composing) working feverishly on it because he had a deadline. It appeared that Stephanie had wrangled a commission for Mozart from the Emperor, specifically for the arrival of the Russian ambassador, Grand Duke Paul, the son of Catherine the Great. The premiere was to have been in September. However, for some typically inexplicably Byzantine political reason, the ambassador did not show up as scheduled, and so the premiere was pushed back. Meanwhile, Mr. Bretzner complained loudly and in the newspapers of his original idea being stolen and plagiarized by Stephanie and Mozart !

During the time Mozart was composing Die Entführung, he wrote a revealing letter to his father about the nature of opera, stating that “I would say that in an opera the poetry must be altogether the obedient daughter of the music. Why are Italian comic operas popular everywhere – in spite of the miserable libretti? … Because the music reigns supreme, and when one listens to it all else is forgotten. An opera is sure of success when the plot is well worked out, the words written solely for the music and not shoved in here and there to suit some miserable rhyme ... The best thing of all is when a good composer, who understands the stage and is talented enough to make sound suggestions, meets an able poet, that true phoenix; in that case, no fears need be entertained as to the applause…” (from V. Braunbeherens, Mozart in Vienna: 1781 to 1791, 1990)

|

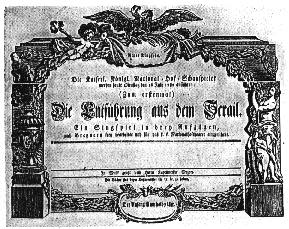

| The opening night playbill of Die Entfürhung at the Burgtheater, Vienna July 16, 1782 |

The premiere of Die Entführung was at the Burgtheater in Vienna on July 16, 1782 and it was an unqualified success. There were rave reviews. For a short time, Mozart became the rock star operatic composer that Handel had been fifty years earlier. Emperor Joseph II had found his “UberSingspiel-Komponist” (“Over-the-top Composer of Singspiel”), if you will. Even though the Nationalsingspiel project was ultimately given up as a failure, Mozart's Die Entführung emerged as its exemplar. It was performed repeatedly in Vienna and German-speaking Europe. The Emperor, who actually was quite musical (unlike the all-thumbs musical duffer he was portrayed as in Milos Forman and Peter Schaeffer’s movie Amadeus), was astonished by the sheer inventiveness and brilliance of Mozart’s effort. The story goes (as per Mozart’s first biographer Franz Xavier Niemetschek) its Niemetschek in 1798) that the Emperor went up to Mozart after the premiere and remarked, “That is too fine for my ears. There are very many (too many) notes, Herr Mozart.” To which Mozart replied, “There are just as many notes as should be.”

The supreme German poet and author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe greatly admired Mozart, fifteen years his junior. When Goethe was director of the Theater at Weimar from 1790 to 1795, he had Die Zauberflote produced over a hundred times. Goethe, just as Mozart before him, was determined to make German Singspiel an art form on a par with Italian opera, and to that end wrote six Singspiele of his own between 1781 and 1784. Along the way, Goethe heard Die Entfhürung and commented that "all our endeavors (in Singspiele)... to confine ourselves to what is simple and limited were lost when Mozart appeared. His Die Entfhürung has conquered all....

|

| Aleksandra Kurzak as Blondchen and Kristinn Sigmundsson as Osmin Metropolitan Opera 2009 |

Then there are the incredible virtuoso arias – especially those for Konstanze and Belmonte, the heroine and the hero – among the most beautiful and most difficult in the whole operatic literature. Mozart was blessed with remarkable sopranos during his compositonal life, In this case it was the sublime Catarina Cavalieri, whom he cast as Konstanze. Cavalieri, who among other things was Antonio Salieri’s lover, apparently had a crystalline voice of almost three octaves, and Mozart duly wrote arias both to suit her tessitura and challenge her artistic skill. Mozart in fact had said that he had written some “bravura Italian arias,… for the flexible throat of Mlle. Cavalieri.” Konstanze’s first aria, a ten minute symphonic tour de force which appears to have been airlifted from one of his opera seria efforts and plopped down smack dab in the middle of this lovely farce, is the showpiece Martern Aller Arten, which Beverly Sills famously nicknamed Aller Fall Aparten ! Fiendishly difficult even for the best coloraturas, it has challenged sopranos for over two centuries, which is a reason why Die Entführung is not performed very often. A famous soprano was once asked which aria was the most difficult to sing in all of opera. She immediately responded, “Why, Konstanze’s aria, Marten aller Arten of course .... (pause).... and that is only because Konstanze’s other aria, Ach, ich liebte, is unsingable !”

Belmonte has four world-class arias, heroic songs of such poignancy and longing that although they are for a tenore leggiero Fach (a light tenor musical range), one can see how they would eventually transfigure into the Heldentenor arias in Fidelio and the Wagnerian operas. There is also an eerily prefigured harkening in these Belmonte arias to those of Tamino nine years later in Die Zauberflöte. (The Magic Flute). In fact, there are many parallels and symmetries between these two Sinsgspiels – the couples Belmonte and Konstanze going through their own trial by fire, morphing into Tamino and Pamina; Blondchen and Pedrillo are transmuted into Papageno and Papagena, Osmin becomes Monostatos, Pasha Selim is kindred spirit to Sarastro. Only Die Königin der Nacht, the Queen of the Night, remains unpaired, as she should be.

One of the most revelatory moments in Die Entführung occurs at the end of Act Two. At this point in the opera, four of the principals - Belmonte, Konstanze, Blonde and Pedrillo - find themselves alone. They each begin singing, as if to themselves, but then, magically, Mozart interweaves them as a quartet, an ensemble of blended voices that begin to have a conversation. This Act Two quartet is one of the first true ensemble pieces ever written in opera. Until then, virtually all operatic arias were solos or at most duets. It is a transformative moment in operatic history. In addition, both Belmonte and Pedrillo question the fidelity of their lovers, Konstanze and Blonde, foreshadowing the same eternal question that is at the epicenter of that later and sublime Mozartean opera of genders, Cosi fan Tutte.

Then there is the matter of Osmin. Oh yes, Osmin, the emblematic bad guy (there is almost always a bad guy in opera). Die Entführung can only be staged if a company has a great Osmin (Kurt Moll comes immediately to mind). That is because Mozart, ever the pragmatist and opportunist, took advantage of the presence of a splendid bass in his midst, one Ludwig Fischer, who sang Osmin in the Vienna premiere with Madamoiselle Cavalieri. Among Osmin’s feats is his great aria “O wie will ich triumphieren” where in several places the bass has to sing down to a D2, that is, a D almost two octaves below middle C ! There is virtually nowhere else in the operatic literature that demands that low a note from its basso profondo.

Many devotees of Die Entführung have long and wistfully wondered why Pasha Selim does not sing – his is a pure speaking role in the opera. In the parallel to Die Zauberflöte, Pasha Selim would be aligned with Sarastro. Sarastro has two magisterial arias. So, why doesn’t Pasha Selim have at least one? Would Mozart really turn over in his grave if, as John Yohalem posits in Opera Today, a Zaide aria was “borrowed” for Selim? Doubtful. Or, maybe, one of Belmonte’s four somewhat repetitive arias was given to the eternally songless Pasha? We shall never know.

Die Entführung became a very successful opera in the decade Mozart lived in Vienna and in the years after he died. With time, the opera faded from view, and was only periodically revived. The key reason for this was the demanding nature of the arias, but the other issue was that the opera, and Singspiel in general, wasn't considered truly "Grand Opera," in the Wagnerian tradition that was to come. Later, much later, in the early twentieth century, Die Entführung was resuscitated and enjoyed a flowering in mid-century with many splendid and fine performances. It is a more commonly performed opera today than at any time since the years after its premiere.

Die Entführung became a very successful opera in the decade Mozart lived in Vienna and in the years after he died. With time, the opera faded from view, and was only periodically revived. The key reason for this was the demanding nature of the arias, but the other issue was that the opera, and Singspiel in general, wasn't considered truly "Grand Opera," in the Wagnerian tradition that was to come. Later, much later, in the early twentieth century, Die Entführung was resuscitated and enjoyed a flowering in mid-century with many splendid and fine performances. It is a more commonly performed opera today than at any time since the years after its premiere.

|

| The unfinished 1782 oil of Mozart by his brother-in law Joseph Lange |

With Die Entführung, Mozart again proved himself to be the consummate composer - innovative, pragmatic, clever and sophisticated - in short, the genius that he was in every musical genre.

Die Entführung is a winner of an opera, with brilliantly conceived music and with melodies which presage Mozart's own transcendant Die Zauberflöte, making it too a masterpiece.

Die Entführung is a winner of an opera, with brilliantly conceived music and with melodies which presage Mozart's own transcendant Die Zauberflöte, making it too a masterpiece.

Copyright 2012 Vincent de Luise MD A Musical Vision

That is incredibly wonderful to read. It is brilliant.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much ! I am glad you enjoyed it.

ReplyDelete